Recently I saw some pretty impressive dinosaur remains that evade description. These are tough. They're even stumping me, believe it or not.

Of course they are hips.

Sauropod hips are usually pretty easy to identify. The basal ones are pretty simple, relatively small ilium and the ischium and pubis of similar length and lightly built.

![]() |

| Eomamenchisaurus yuanmouensis |

Then you have diplodocoid hips, which have big rounded ilia and very tall sacral spines:

![]() |

| Diplodocus longus |

Camarasaurs have similar ilia but much squatter and even more completely fused sacrals.

![]() |

| Camarasaurus supremus |

Brachiosaur hips are relatively rare in the fossil record (or at least complete described and published ones seem to be). Overall they are wide and extensively fused in the sacrals to support more weight, and have tall ilia with the front end much larger and taller than the back end.

![]() |

| Brachiosaurus altithorax (sacrum). Note the hypantrum gap at the front of the sacrum, and flat-topped prezygapophyses on either side of it. This will be useful later. |

![]() |

| Brachiosaurus altithorax (right ilium) |

And then you have titanosaur hips, which always tend to be super-wide (in this case even wider than they are long) and super-heavily fused. The ilia are flared out to a downright crazy extent, so the rib cage would have been easily twice as wide as most of the earlier sauropod types. These giants just seemed to be getting fatter and fatter every few million years as the Cretaceous ground on.

![]() |

| Futalognkosaurus dukei complete pelvis (ventral view) |

![]() |

| Futalognkosaurus dukei complete pelvis (front view) |

And then of course you have the stuff that can only border on fantasy:

![]() |

| not sure if this ever was a dinosaur sacrum, or just a weird rock... |

Okay, so on to the star attraction. A few pics from Heinrich Mallison's

blog caught my eye, I had never seen these before and apparently they are from the

Utah Field House of Natural History State Park Museum in Vernal, Utah. We're talking basement vault stuff, locked away far out of view of the museum visitors.

![]() |

| two whatchamacallits... seriously these are weird. |

Neither one of these two specimens have been formally described or assigned to any known species.

The pelvis on the left, on the green-tinted forklift pallet, is obviously the taller and less squat of the two. The ilia still flare out a bit and it appears rather front-heavy, so this may be a brachiosaur or a basal titanosaur. The Potter Creek ilium discovered by Jensen (1985) in Utah also seems to have a mix of features from both groups, and may belong to an intermediary family.

The pelvis on the right is far flatter and more interesting. Its neural spines look a bit Giraffatitan-like but that's where the similarity ends. This pelvis is very wide with super-flared out ilia. Most likely a titanosaur. But lets look closer (keep in mind there's only one species of true titanosaur known from Utah, or the entire United States for that matter).

![]() |

| The squat pelvis from the front. Note the tight space between the prezygapophyses, and the fact that it's a good bit above the neural canal | | | |

|

This thing definitely looks like a titanosaur, but not any that I've seen. A tight, high hypantrum with enough clearance above the neural canal to accommodate a real hyposphene from the final dorsal vertebra (basal titanosaur trait), yet extremely wide hips with super-flared ilia (derived titanosaur trait).

How does it stack up?

![]() |

| Alamosaurus sanjuanensis (referred big bend specimen - pelvis cast, dorsal view. Note the neural spines are separate at the tip - beware that this may be a speculative reconstruction because in many drawings you see them looking fused) |

|

|

|

![]() |

| Trigonosaurus pricei partial pelvis, dorsal view. Once again, note the neural spines are distinctly separate at the tip. |

|

|

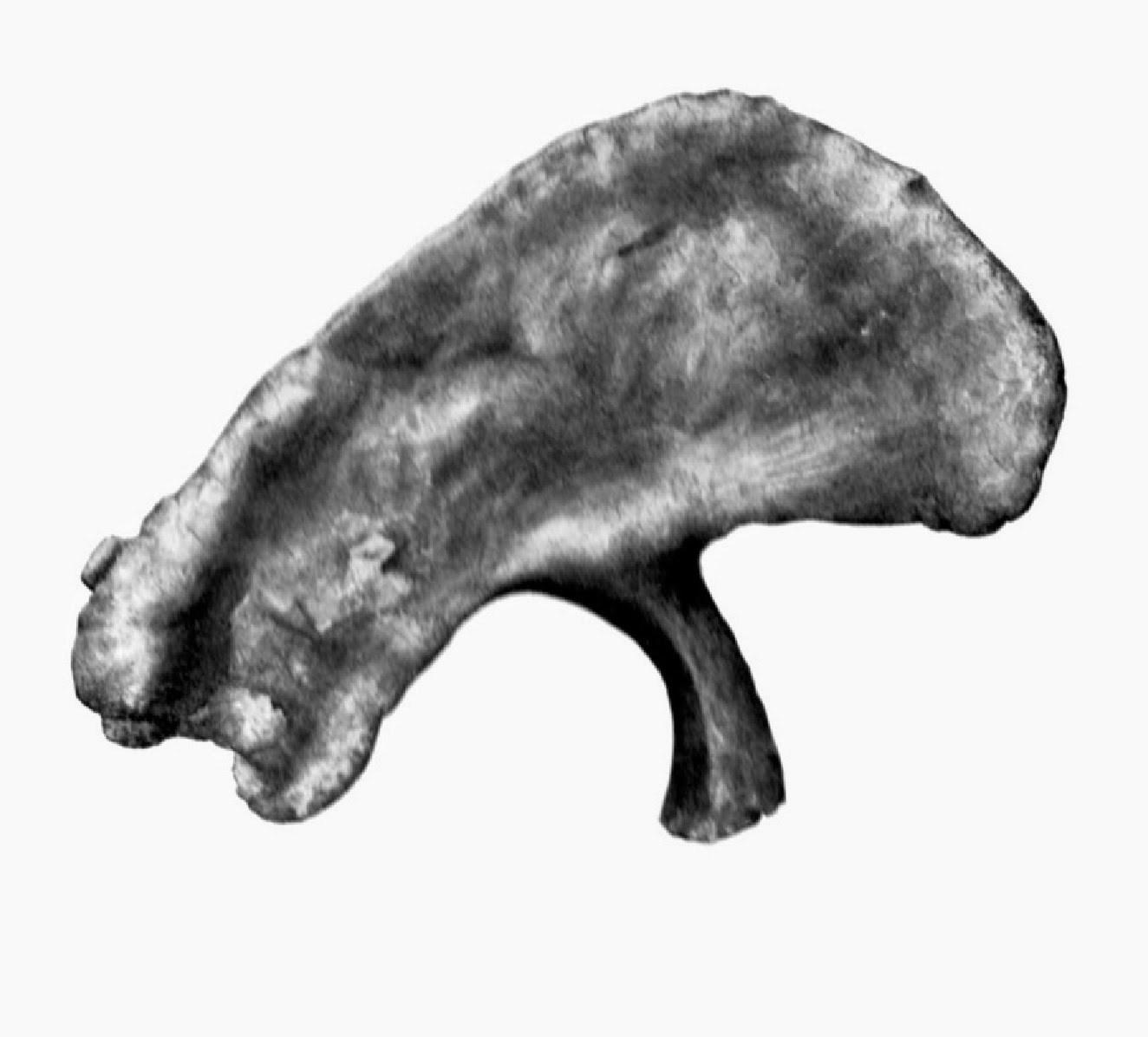

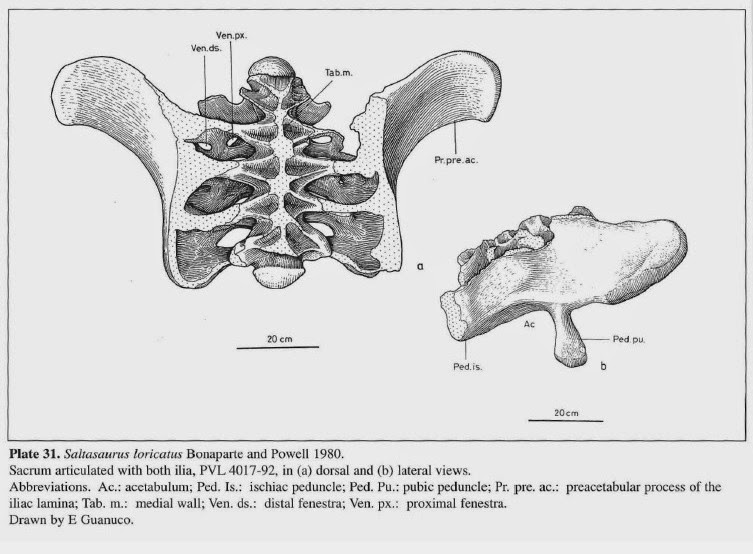

![]() |

| Saltasaurus loricatus pelvis - the neural spines and top of the ilia and sacral rib connections are eroded, but you can still see that the neural spines were configured as having distinctly separate tips. |

![]() |

| Malawisaurus dixeyi - sacrum from above and below. A transitional titanosaur. Note the HEAVY fusion of the neural spines into a single piece by ossified ligaments. |

![]() |

| Huanghetitan liujixiaensis sacrum, anterodorsal view. A basal titanosauriform. Note the fusion of the neural spines by ossified ligaments (though the sides of the tips are still visible), and the gap at the front between the prezygapophyses - it's not as tight as in the Utah pelvis. But like the Utah pelvis, their upper surfaces are flat and horizontal. |

![]() |

| Euhelopus zdanskyi pelvis and last few dorsals. Top view. The backswept ischia are visible at bottom. Note the lack of fusion in the neural spines tips. This animal was intermediate between brachiosaurs and titanosaurs, and slightly more derived than Huanghetitan - yet the neural spines are radically different. However this is an immature animal, and in adults they may have fused with ligaments into a single piece as in Huanghetitan (whose holotype, though much larger, is ironically also not fully grown). |

![]() |

| Unnamed Brazilian titanosaur pelvis - note the heavy fusion of the neural spines with ossified ligament. Also the gap between the prezygapophyses is shallow, and not very far above neural canal. The opposite condition to the Utah pelvis. |

|

|

|

|

![]() |

| Futalognkosaurus dukei pelvis - outlined to clearly show the structures. Note that the prezygapophyses are just above the neural canal, not much clearance, and the gap between them is shallow (just as in the Brazilian taxon), and the connection surfaces are v-shaped. |

And finally... the Utah pelvis again:

![]() |

| Note that the prezygapophyses are deep and block-like, their upper connecting facets are horizontal, not v-shaped, and the gap between them is tall and being "hugged" in a tight embrace, well above the neural canal, as if interlocking with a deep hyposphene on the vertebra in front of it. This isn't found in derived titanosaurs like Futalognkosaurus and the Brazilian titanosaur, which lost the hypantrum-hyposphene feature. |

|

|

So we have the Utah pelvis having some basal traits (brachiosaur-like neural spine "fan-tips" and well-developed deep and high hypantrum which interlocked with a big hyposphene on the last dorsal in front of it) as well as some traits of derived titanosaurs (extremely wide flaring in the ilia and largely unfused neural spine tips as in

Trigonosaurus and

Saltasaurus - yet this latter trait is also present in the far more basal

Euhelopus). Yes, they are mostly unfused at the tips in this sacrum. Here's the proof: a panoramic 3D model by Heinrich Mallison.

![]() |

| The middle four spines are tightly packed together (a common feature of many sauropods) but the tips are still distinct and are not fused into a single straight-edged block like Malawisaurus or the unnamed Brazilian taxon. |

|

|

Overall the shape of the sacral spines and the twist in the sacral ribs reminds me of

Giraffatitan, with the front and middle spines less completely fused, but this is clearly a much wider set of hips.

Whatever this animal is, it looks like a basal titanosaur, but with the extremely wide hips of a derived one. Things get even more complicated when you realize that there's only one true titansoaur known from the United States (and it's native to Utah too),

Alamosaurus. A very derived titanosaur which did NOT have a hypantrum-hyposphene connection. Critically, it was an immigrant from South America, at the time when the land bridge of Panama took shape (Late Cretaceous, Campanian epoch) - before this the two continents were isolated, and North America was known to be nearly devoid of sauropods - the basal titanosauriforms of the Early Cretaceous (

Venenosaurus, Paluxysaurus, Brontomerus, etc.) had already gradually died out. So the Vernal pelvis is clearly no

Alamosaurus. But what is it?

Are we looking at a basal titanosauriform somewhere on the family tree between brachiosaurs and true titanosaurs? Perhaps a

Phuwiangosaurus or

Paluxysaurus-like creature? Or is this a derived titanosaur similar to

Trigonosaurus, with a ridiculous level of throwbacks to its hypantrum-bearing ancestors? In the absence of knowing the creature's age (which would be a big key to figuring out its relationships given the big sauropod-devoid Mid-Cretaceous time gap in North America), what can we deduce from the fossil itself?

And what's more, is this animal a totally "new" species, or a more complete specimen of something we already knew about?

YOU DECIDE... I'd like to see everyone's thoughts.