Recently there's been a huge re-ignition of the sauropod neck debate. Originally it was a debate between whether sauropod necks were normally held vertical for high browsing, or horizontal for low grazing (I'd say that's a moot discussion unless we know precisely which sauropods we're talking about, but so goes the watering-down of the subject in the media...). Well now there's a third voice in the debate, and it's in some ways both the most radical and the most obviously practical of the three: the "necks for sex" hypothesis.

Basically there are some paleontologists in the field who argue that the length of sauropod necks had nothing to do with increasing the "feeding envelope" or feeding radius of the animals, but was basically a sexual advertising signal, much like peacock feathers or perhaps hadrosaur crests. Now if you can forgive the flagrant phallic symbolism of such a theory, it actually seems to make a lot of sense. Giraffes, it's been argued, evolved long necks as a result of sexual selection, not for increasing their feeding envelope. Says Dr. Darren Naish:

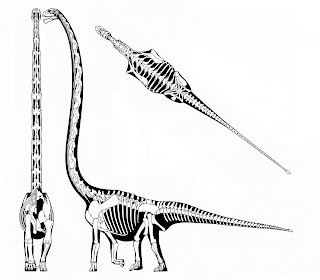

![]() In a well argued and extremely popular* Journal of Zoology article, Phil Senter wondered whether sauropod necks might also have evolved under pressure from sexual selection, and not because of any ecological benefit that they might have incurred (Senter 2007) [adjacent figure - from Senter (2007) - shows that surprise!! sauropods have long necks relative to theropods**. The reconstructions are by Greg Paul]. Senter put forward six predictions that - if validated - would indicate the importance of sexual selection in the evolution of the sauropod neck, most of which related to the possibility of sexual dimorphism, the use of the neck in dominance or courtship displays, its redundancy as an adaptation for increased reach in feeding, and allometric increase in neck length across ontogeny and phylogeny. His conclusion was essentially that, yes, the sauropod neck likely evolved primarily under sexual selection pressure (Senter 2007).."

In a well argued and extremely popular* Journal of Zoology article, Phil Senter wondered whether sauropod necks might also have evolved under pressure from sexual selection, and not because of any ecological benefit that they might have incurred (Senter 2007) [adjacent figure - from Senter (2007) - shows that surprise!! sauropods have long necks relative to theropods**. The reconstructions are by Greg Paul]. Senter put forward six predictions that - if validated - would indicate the importance of sexual selection in the evolution of the sauropod neck, most of which related to the possibility of sexual dimorphism, the use of the neck in dominance or courtship displays, its redundancy as an adaptation for increased reach in feeding, and allometric increase in neck length across ontogeny and phylogeny. His conclusion was essentially that, yes, the sauropod neck likely evolved primarily under sexual selection pressure (Senter 2007).."

It's a pretty tempting theory. But the fact is, giraffe necks do provide benefits in browsing range. And their high shoulders also give them an additional height boost for high browsing. Is all of this simply a coincidence of sexual selection? Dr. Naish doubts the "necks for sex" theory, and I have to agree with him. Evolving long necks as a purely sexual display device just isn't an efficient strategy. Consider that in birds, it's feathers that get highly modified for sexual display, not the energy-hungry flesh-and-bone parts of the body. Sauropods lacked feathers (or so we're pretty sure!) but they might have had dorsal spines for display. Diplodocus is known to have them, though whether they got truly huge in any species is unknown. Also, with their huge bodies, all that surface area on sauropods might have been brightly colored for sexual display. (As a side note, Allosaurus actually has a pretty long neck for a large theropod - probably to add extra lunging range to make up for its relatively short snout.)

What DID sauropods find sexy?

"Necks for sex" may explain a lot of the odd variations in sauropod necks, which often differ radically from one species to the next. But when thinking about how basic flesh-and-bone structures can become so elongated, I have serious doubts that animals would go through such a heavy expenditure of resources only for sexual selection. After all, that neck needs a lot of oxygen, needs blood, muscles, nutrients, etc. and that's a huge energy demand - it's not just a simple matter of producing a few ounces of keratin here and there like with colorful bird feathers. Nobody has ever suggested that large fleshy structures like elephant trunks or whale flukes are purely there for sex - they serve far more immediate utilitarian purposes - one for gathering food, the other for movement. And once you consider structures that contain both flesh and bone, like long necks... the expenditure of nutrients goes even higher. Calcium for bones, prodigious amounts of L-Arginine for lean muscle, Glycogen for tendons, glucosamine for cartilage disks, huge amounts of sugar compounds for maintaining the massive connective tissues, all the myelin that's needed to coat all the miles of nerves in that neck... all things that require a huge additional amount of food to produce, things that you simply don't need for pure sexual display structures like peacock feathers. Having long necks purely for sex just doesn't seem worth the huge cost of resources. It's a lot easier to grow long external dorsal spines, or simply be colorful, than it is to develop a long neck just for sex.

But then this begs the question - if we supposed for a moment that an intense form of neck-based sexual selection was going on in sauropods, what exactly was being selected for? Only the longest neck possible? If so, why is there such a differing range of sauropod neck sizes?

As you can see, the sauropod necks are not all of the same length. Different genera have radically differing neck lengths, thicknesses, and anatomy. Did it all come down to females preferring different neck lengths in males across different species? Did Apatosaurus females simply prefer shorter necks than Brachiosaurus females, and thicker ones than Diplodocus females? Were Barosaurus females just that much more picky and hard to please than Diplodocus females, so that despite being so similar in most other aspects, the neck of Barosaurus ended up becoming 50% longer than that of Diplodocus?

I don't know, but that seems an awfully wimpy cop-out explanation to a very scientific problem. You can't simply blame everything on the woman :) Maybe female sauropods did have some pretty odd preferences which were far from consistent across genera. But maybe their tastes had nothing to do with neck size, but rather bright colors or pheromones. Heck, maybe it was even the males that were picky, not the other way around. Being a very big social animal does have certain advantages for experienced males, as anyone who's studied elephants and sperm whales is well aware - the mature bulls get to do all the picking. But in any case, the amazing array of neck lengths, neck thicknesses, neck depths, vertebra counts, and head sizes, is something that I find pretty difficult to explain away simply with sexual selection. And this isn't even the full gamut of sauropod necks. Some are downright bizarre. You've got squat, wide cross-section necks like in Phuwiangosaurus, Puertasaurus, Alamosaurus, and a host of other titanosaurs (the trait probably evolved multiple times). You've got hefty deep necks like Futalognkosaurus. You've got the weird short high-spined necks of Dicraeosaurus and Amargasaurus. You've got the crazy-long, as in Mamenchisaurus, Sauroposeidon, Daxiatitan, and the somewhat more cuddly Euhelopus, the obscenely long, as in Erketu, and then the crazy-short, as in Bonitasaura and Brachytrachelopan. And then you've also got this:

One of the weirdest sauropods in terms of proportions, this is Isisaurus colberti (partial skeletal by Jaime Headden). A mid-sized titanosaur with a crazy-deep monster of a neck that logically doesn't have any good explanation other than sexual display. As much as 75% of the height of each vertebra is made up by the neural arch! Not only that, there are some downright freaky things about the hips and torso (look at those super-flat ilia, that enormously deep chest, high shoulders, and the obscenely long pubis - it even looks like a sex beast!) And then there are the arms, which seem to be all humerus! Now to be fair Jaime has previously said that this skeletal has some proportion issues and is not as accurate as it could be, but all the same it's well known that Isisaurus was one weirdly proportioned dinosaur. And at the very least, one of the most extreme necks ever known. That thing was a walking billboard. The neck isn't unusually long for a sauropod (though if the published data is any clue, it was longer than either the torso or the tail). But its extreme depth (along with all the other odd proportions) serves no apparent biomechanical purpose, and it really could only be a product of sexual selection, with the tall spines turning it into a huge display device. Isisaurus was also one of the last dinosaurs to have lived, roaming the jungles of a then-isolated India in the Maastrichtian, right at the end of the Cretaceous. If dinosaurs had not gone extinct 65 million years ago, one can only imagine how much stranger Isisaurus' descendants could have gotten.

While it's entirely possible that some aspects of neck anatomy may indeed have been the result of sexual selection (especially tall neural arches or spines/sails) I doubt that the length or actual mechanics of the neck were influenced so much by sexual selection as by feeding niches. When you lengthen a functional body part like a neck, especially considering it has your head and mouth at the end of it, there are also very practical, non-display considerations.

For example, if you're a ground feeder with peg-shaped teeth and a square "vacuum cleaner" jaw adapted for nipping low ferns, you're probably going to develop a neck which can be held horizontally or even drooping down for long periods of time, and would not be so long as to make maneuvering difficult in at least lightly forested areas. Ordinarily this would put a lot of strain on the neck, but the diplodocids had a way of compensating for this problem - their posterior neural spines were not just heavily forked to support a twin system of cable-like nuchal ligaments - they were also taller relative to vertebra length than on most other sauropods, and heavily angled forward with prominent ball-like ends to add extra leverage to the tendons pulling them back. Thus even in a relatively relaxed position, the nuchal tendons could effectively keep the neck horizontal without over-exerting themselves. The "canyon" between the double rows of neural spines likely included a third, auxiliary set of ligaments, though the knobs which anchored them at the base of these grooves are only prominent in a few genera. This middle tendon was likely not deep enough to entirely fill the space between the double rows of neural spines in diplodocids, and certainly not in dicraeosaurids.

However, if you're a high browser with large heavy teeth and a rounded snout adapted for foraging in the trees, then a long neck is an ideal tool for high feeding in the trees.

In fact it used to be popular to think that all diplodocoids had horizontal necks, all macronarians had vertical necks, etc. Now there is research that disproves both notions. Whitlock has recently come out with a paper that shows that many diplodocids had rounded snout tips and tooth wear patterns consistent with feeding on conifers - including barosaurs like Tornieria and, strangely enough, short-necked dicraeosaurs too (they were probably rearing to feed on the lower branches of the conifers, as they could not reach very high even when rearing). However Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, and Nigersaurus all have square mouths and tooth wear consistent with feeding on low ferns. Nigersaurus seems to have fed exclusively on low ferns, due to its awesomely wide "vacuum cleaner" mouth. It's doubtful this animal ever fed on tough conifers, though it was capable of rearing. It was basically a dinosaurian cow.

Where else do we see this dichotomy of high-browsing rounded mouths and low-grazing square mouths?

Camarasaurus, Brachiosaurus, Euhelopus all have rounded mouths/snout tips and big heavily worn teeth - the mark of a high browser (and in the case of the huge-mouthed Brachiosaurus and Giraffatitan, a not particularly picky high browser).

But there are some macronarians which have actually "broken the rules" of their clade to become low-grazers and fill in some of the fern-eating niches left vacant in the Cretaceous by the now-extinct diplodocids. Some derived titanosaurs, notably the short-necked Saltasaurus and the even shorter-necked Bonitasaura, have a very diplodocid-like head, and more importantly, square mouths. Antarctosaurus has an extremely wide "vacuum cleaner" mouth that is a remarkable case of convergent evolution with rebbachisaurids like Nigersaurus. All had square snouts and mouths. Yet remarkably, some of their close relatives, the nemegtosaurids, have far longer necks and narrower, round-tipped snouts suited to high browsing. This is a major parallel with the differences of snout design and feeding habits of Diplodocus vs. Barosaurus. It seems that in many different lineages of sauropods, there were both low grazers and high browsers.

Hint: it's neither for gluttony nor sloth nor lust

However, there's one constant factor (at least more or less constant within most families) that often gets missed. Neck length. Sauropods with vertical feeding habits tend to have much longer necks that low fern eaters - even if they're close relatives. Longer necks are not simply an adaptation for increasing a horizontal ground-level feeding envelope the way proponents of the SNAFU theory ("Sauropod Necks Are Forever Underslung") seem to insist. Barosaurus and Tornieria were high-browsers and they had much longer necks than Diplodocus or Apatosaurus. Furthermore, Apatosaurus is easily twice the mass of Diplodocus, yet has a neck of equal or sometimes shorter length - which proves that as mass increases (and thus your food needs increase) a low-grazer can still consume enough food without needing a proportionally longer neck. In other words, having an extremely long neck when you're a low-grazer is actually a WASTE of precious nutrients and resources that you could be using to feed a bigger body, grow faster to deter predators, etc. As a low-grazing species, once you hit a certain neck proportion, you can get bigger and still keep your neck relatively short (like Apatosaurus) and not have to worry about increasing your feeding envelope beyond that of a far lighter animal like Diplodocus.

Is it really all that hard, after all, to just take a few steps forward when you've consumed everything in your grazing envelope? I thought we'd long moved past the days when sauropods were seen as lazy, lethargic slobs that could barely move their bums at all. The expense of resources for growing a very long neck is too high to justify the increase in feeding envelope size for a sauropod that wasn't even feeding above shoulder level - after all, the limits of lateral mobility on sauropod necks mean that the posterior 75% or so of a horizontal feeding envelope is actually out of reach to a low-grazing sauropod, since the neck can't bend back over its own length like a snake. So the increase in feeding envelope range for horizontal low-grazers with longer necks is marginal at best, since a horizontal feeding envelope isn't really a horizontal cone as commonly depicted in papers - it's more like just the lower half of the base of that cone! A marginal arithmetic increase in this narrow sub-oval arc doesn't justify the huge exponential upfront resource cost of ever longer necks just to avoid the inevitability of having to walk a few steps forward, and that's probably why Apatosaurus's neck was no longer than that of Diplodocus despite being a far more massive and therefore energy-hungry animal. Longer necks are not simply a slothful luxury for low-grazers to get a few more bites while avoiding a few more steps - as such, they would be woefully inefficient in terms of huge extra resource cost vs. the relatively meager benefit of having to walk less - rather, they are an adaptation for something far more specific, something that low-grazing, square-mouthed "vacuum cleaner" diplodocoids didn't even mess with.

In fact, it's not that far-fetched to say that ALL extremely long-necked sauropods were high browsers. Anything like Brachiosaurus, Giraffatitan, Euhelopus, Omeisaurus, Mamenchisaurus, and many titanosaurs, both basal and derived, would be a high-browser with a neck capable of vertical posture. They all have either massive teeth for crunching through branches, or in the case of barosaurs and nemegtosaurs, tooth-wear patterns and snout shapes that suggest high browsing, perhaps of a more finesse-bound sort. None of these animals have the sharply angled square snout typical of low-grazing fern-eaters.

And logically, an extremely long neck would make maneuvering difficult in tall forests unless it was held vertically or at least semi-vertically. Extremely long tails would make movement in the forest difficult for high-browsers as well, and tails could not be pointed vertically - most high-browsing sauropods simply reduced them. Brachiosaurs are the most extreme example, but there are others. No mamenchisaur or "euhelopodid" ever had a tail comparable in length to that of Diplodocus. And even Barosaurus had a shorter tail than Diplodocus, though both animals were roughly the same size and both had a whip-like tail ending. Thus, extremely long tails (and comparatively short necks) seem to be mainly a feature of low grazing sauropods that fed on the open fern plains, whereas high browers increased the neck (and its typical incline) while reducing the tail, to get at a greater vertical range of food while avoiding getting stuck in the forest. If a complete Supersaurus skull is found, it will probably fit the pattern of high-browsing diplodocids like Barosaurus, even though it's an apatosaurine. It's got the very long neck and relatively modest tail proportions of Barosaurus, and it probably was capable of the same high-browsing behavior - and probably a rounded snout.

But what about camarasaurs? They have short necks which can articulate vertically, and they have the snout and teeth of a high-browser - why are their necks not longer? Likely they were not browsing all that high. Like dicraeosaurs, their reach was limited, but could be augmented by rearing. However, it's worthy to note that the teeth of Camarasaurus are more heavily worn than those of some high-browsing sauropods with longer necks. Microwear analysis of these, according to Bakker (1986) indicates they were eating very gritty food, perhaps the result of seasonal dust storms which left grit on the lower levels of conifer trees. As most dust is too heavy to be carried very high, the higher parts of the trees were free from it and caused moderately less wear on the teeth of taller high-browsers. Another possibility is that Camarasaurus was simply a mid-level browser, not a high-browser, and fed on very tough plants like large cycads and the dry lower branches of conifers.

Size and food intake requirements really have nothing whatsoever to do with neck length. "Omeisaurus" tianfuensis is even lighter than the mere 11-ton Diplodocus, yet has a phenomenal neck that absolutely puts it to shame (not to mention Apatosaurus, which weighed roughly 20 tons). Perhaps you could argue that Omeisaurus' crazy-long neck gave it the advantage of a huge vertical AND horizontal feeding envelope - after all, vertical necks imply a full-circle hemispheric feeding envelope, which gives access to far more food at any moment per additional meter of neck than a horizontal wedge-shaped one, regardless of neck flexibility. But in all likelihood, "Omeisaurus" probably didn't need an envelope so big. It was smaller than Diplodocus, (let alone Apatosaurus!) which made do with a much smaller feeding envelope and far less vertical range. Even feeding the extra energy and blood requirements of such a long neck (which might have proved prohibitively high for a low-grazing diplodocid with far tighter vertical limits on its diet and feeding envelope) probably wouldn't require full use of the huge feeding envelope of "Omeisaurus" at every step it walked. After all, the feeding envelope of a 9-ton Omeisaurus was many times the size of that of even a 20-ton Apatosaurus, and far taller as well! It's inconceivable that the neck and heart alone, no matter how large, would somehow use up more nutrients than the 11 additional tons of flesh and bone found in Apatosaurus! So it's unlikely that increasing the feeding envelope was the sole driving force behind some vertical-necked sauropods developing extremely long necks, because many of them probably did not need the entire vertical-capable feeding envelope to meet their energy needs, even with the colossal neck and the powerful heart it required.

The only remaining logical reason for such a dizzying neck is not simply to reach every plant within a vertical-capable neck's entire hemispheric feeding envelope, but to reach a particular food source beyond the reach of shorter necks - most likely the treetops. Extremely long necks are found in both small sauropods like Euhelopus and mega-giants like Sauroposeidon and Puertasaurus. Likewise, relatively short necks are found both on dwarfs like Saltasaurus and giants like Apatosaurus (well, moderately giant anyway). Neck length is more indicative of the type of food you ate and where it was, not how much of it you needed.

End result: Mamenchisaur necks vertical, Macronarian necks vertical (except for saltasaurids and a few other derived titanosaurs), diplodocid necks horizontal (possibly except barosaurines and Supersaurus) and dicraeosaurid necks horizontal but still vertical-capable by rearing. BTW the diplodocid neck mechanics of barosaurs and Supersaurus still would not allow as sharp an incline as in most macronarians. They could have curved the neck up at roughly 45 degrees or reared up like other diplodocids to get at the very high branches. While rearing, these high-browsing diplodocids would have towered over even Brachiosaurus.

Long story short, necks may have served a sexual display or species recognition function, but that alone is insufficient to explain actual neck length differences, which are largely feeding-related. Sex alone cannot justify the vast expenditure of nutritional resources needed for developing some of the longest sauropod necks, as these were energy-costly flesh, blood, and bone structures, rather than simple keratinous cosmetic features like peacock feathers, which are not an integral part of internal anatomy and require far less food intake to maintain. Though sauropod necks were not long simply for sexual reasons, some secondary features of the living neck (such as color and possible display spines) may have had a sexual display purpose. Also, unusual neck width and depth are likely sexually selected display features, particularly in extreme forms like Isisaurus. However, functional length and flexibility were likely free of sexual driving forces for the most part, and were more driven by feeding specializations. Very long necks for high browsers, shorter ones for medium or low browsers. Low shoulders + relatively short neck usually equals low-grazer, but not in the case of Dicraeosaurus. Ultimately, skull and snout shape is one of the best gauges of sauropod feeding habits, and indicates that very long necks are always associated with high browsers, but that not all shorter necks are those of low-grazers.

Of course, Taylor, Wedel, and Naish (2009) have already pretty much busted the myth that sauropods couldn't have raised their necks vertically. They showed (using biomechanical comparisons with living animals, no less!) that sauropod necks can have a substantial range of articulation in each joint well above Osteological Neutral Pose - these were flexible ball-and-socket joints, not stiff flat-ended ones. Indeed, for low-spined forms with very long necks like brachiosaurs and mamenchisaurs, a vertical posture would be far easier to hold up than a horizontal one since the shallow nuchal tendons would be quickly strained in a horizontal posture - imagine holding a long pole at one end horizontally, you can't. Vertically, you can, since gravity is now working with you, not against you. Simple. Diplodocus managed a horizontal posture thanks to its deep and strangely forward-angled "cantilever" neural spine yokes, giving more passive leverage to the nuchal tendons to keep the neck in a horizontal position without over-straining. Barosaurus is an odd case - with its longer neck, would have probably had a steeper habitual neck posture (as illustrated in Paul, 1998) to minimize strain, but the same cantilever design in its lower cervicals meant that they too started off horizontal as in Diplodocus. If it fed while rearing (which was very likely) it would reach great heights without needing to deflect the neck up relative to the back.

In other words, proportional neck length is related to feeding niches, not sex or size/calorie requirements. Long necks for high browsers, shorter ones for medium and low browsers. Macronarians and mamenchisaurs likely used vertical posture to reach food at their particular browsing level, while diplodocoids either reared to reach high, or didn't even bother and just stuck to ferns and seedlings. And if you're still drawing your brachiosaurs or mamenchisaurs with droopy horizontal or underslung necks sticking out like a microphone boom on a movie set - crane 'em up!

Basically there are some paleontologists in the field who argue that the length of sauropod necks had nothing to do with increasing the "feeding envelope" or feeding radius of the animals, but was basically a sexual advertising signal, much like peacock feathers or perhaps hadrosaur crests. Now if you can forgive the flagrant phallic symbolism of such a theory, it actually seems to make a lot of sense. Giraffes, it's been argued, evolved long necks as a result of sexual selection, not for increasing their feeding envelope. Says Dr. Darren Naish:

"In 1996, Robert Simmons and Lue Scheepers argued that the giraffe neck functions as a sexual signal: they said that the necks of males are bigger and thicker than those of females, that the necks of males continue growing throughout life, that females prefer males with bigger necks, and that giraffe necks don't provide any obvious benefit in vertical reach or foraging range, contra the 'traditional', 'increased feeding envelope' hypothesis (Simmons & Scheepers 1996). This has become known as the 'necks for sex' hypothesis...

"It was only a matter of time before someone published the idea that the 'necks for sex' hypothesis might apply to another group of tetrapods famous for their long necks - namely, the sauropod dinosaurs.

In a well argued and extremely popular* Journal of Zoology article, Phil Senter wondered whether sauropod necks might also have evolved under pressure from sexual selection, and not because of any ecological benefit that they might have incurred (Senter 2007) [adjacent figure - from Senter (2007) - shows that surprise!! sauropods have long necks relative to theropods**. The reconstructions are by Greg Paul]. Senter put forward six predictions that - if validated - would indicate the importance of sexual selection in the evolution of the sauropod neck, most of which related to the possibility of sexual dimorphism, the use of the neck in dominance or courtship displays, its redundancy as an adaptation for increased reach in feeding, and allometric increase in neck length across ontogeny and phylogeny. His conclusion was essentially that, yes, the sauropod neck likely evolved primarily under sexual selection pressure (Senter 2007).."

In a well argued and extremely popular* Journal of Zoology article, Phil Senter wondered whether sauropod necks might also have evolved under pressure from sexual selection, and not because of any ecological benefit that they might have incurred (Senter 2007) [adjacent figure - from Senter (2007) - shows that surprise!! sauropods have long necks relative to theropods**. The reconstructions are by Greg Paul]. Senter put forward six predictions that - if validated - would indicate the importance of sexual selection in the evolution of the sauropod neck, most of which related to the possibility of sexual dimorphism, the use of the neck in dominance or courtship displays, its redundancy as an adaptation for increased reach in feeding, and allometric increase in neck length across ontogeny and phylogeny. His conclusion was essentially that, yes, the sauropod neck likely evolved primarily under sexual selection pressure (Senter 2007).." It's a pretty tempting theory. But the fact is, giraffe necks do provide benefits in browsing range. And their high shoulders also give them an additional height boost for high browsing. Is all of this simply a coincidence of sexual selection? Dr. Naish doubts the "necks for sex" theory, and I have to agree with him. Evolving long necks as a purely sexual display device just isn't an efficient strategy. Consider that in birds, it's feathers that get highly modified for sexual display, not the energy-hungry flesh-and-bone parts of the body. Sauropods lacked feathers (or so we're pretty sure!) but they might have had dorsal spines for display. Diplodocus is known to have them, though whether they got truly huge in any species is unknown. Also, with their huge bodies, all that surface area on sauropods might have been brightly colored for sexual display. (As a side note, Allosaurus actually has a pretty long neck for a large theropod - probably to add extra lunging range to make up for its relatively short snout.)

What DID sauropods find sexy?

"Necks for sex" may explain a lot of the odd variations in sauropod necks, which often differ radically from one species to the next. But when thinking about how basic flesh-and-bone structures can become so elongated, I have serious doubts that animals would go through such a heavy expenditure of resources only for sexual selection. After all, that neck needs a lot of oxygen, needs blood, muscles, nutrients, etc. and that's a huge energy demand - it's not just a simple matter of producing a few ounces of keratin here and there like with colorful bird feathers. Nobody has ever suggested that large fleshy structures like elephant trunks or whale flukes are purely there for sex - they serve far more immediate utilitarian purposes - one for gathering food, the other for movement. And once you consider structures that contain both flesh and bone, like long necks... the expenditure of nutrients goes even higher. Calcium for bones, prodigious amounts of L-Arginine for lean muscle, Glycogen for tendons, glucosamine for cartilage disks, huge amounts of sugar compounds for maintaining the massive connective tissues, all the myelin that's needed to coat all the miles of nerves in that neck... all things that require a huge additional amount of food to produce, things that you simply don't need for pure sexual display structures like peacock feathers. Having long necks purely for sex just doesn't seem worth the huge cost of resources. It's a lot easier to grow long external dorsal spines, or simply be colorful, than it is to develop a long neck just for sex.

But then this begs the question - if we supposed for a moment that an intense form of neck-based sexual selection was going on in sauropods, what exactly was being selected for? Only the longest neck possible? If so, why is there such a differing range of sauropod neck sizes?

Necks of large herbivorous dinosaurs from the Morrison formation, with large mammals for comparison, in vertical feeding posture. From Paul, 1998 (for diplodocids, vertical posture would likely require rearing). A) Apatosaurus louisae in lateral and dorsal view. B) Brachiosaurus altithorax (restored after Giraffatitan brancai). C) Camarasaurus lentus. D) Diplodocus carnegiei. E) Barosaurus lentus. F) Stegosaurus (=Diracodon) stenops. G) Giraffe. H) African elephant. I) Indricotherium, the largest land mammal known in the fossil record. Posted for educational purposes only.

As you can see, the sauropod necks are not all of the same length. Different genera have radically differing neck lengths, thicknesses, and anatomy. Did it all come down to females preferring different neck lengths in males across different species? Did Apatosaurus females simply prefer shorter necks than Brachiosaurus females, and thicker ones than Diplodocus females? Were Barosaurus females just that much more picky and hard to please than Diplodocus females, so that despite being so similar in most other aspects, the neck of Barosaurus ended up becoming 50% longer than that of Diplodocus?

I don't know, but that seems an awfully wimpy cop-out explanation to a very scientific problem. You can't simply blame everything on the woman :) Maybe female sauropods did have some pretty odd preferences which were far from consistent across genera. But maybe their tastes had nothing to do with neck size, but rather bright colors or pheromones. Heck, maybe it was even the males that were picky, not the other way around. Being a very big social animal does have certain advantages for experienced males, as anyone who's studied elephants and sperm whales is well aware - the mature bulls get to do all the picking. But in any case, the amazing array of neck lengths, neck thicknesses, neck depths, vertebra counts, and head sizes, is something that I find pretty difficult to explain away simply with sexual selection. And this isn't even the full gamut of sauropod necks. Some are downright bizarre. You've got squat, wide cross-section necks like in Phuwiangosaurus, Puertasaurus, Alamosaurus, and a host of other titanosaurs (the trait probably evolved multiple times). You've got hefty deep necks like Futalognkosaurus. You've got the weird short high-spined necks of Dicraeosaurus and Amargasaurus. You've got the crazy-long, as in Mamenchisaurus, Sauroposeidon, Daxiatitan, and the somewhat more cuddly Euhelopus, the obscenely long, as in Erketu, and then the crazy-short, as in Bonitasaura and Brachytrachelopan. And then you've also got this:

One of the weirdest sauropods in terms of proportions, this is Isisaurus colberti (partial skeletal by Jaime Headden). A mid-sized titanosaur with a crazy-deep monster of a neck that logically doesn't have any good explanation other than sexual display. As much as 75% of the height of each vertebra is made up by the neural arch! Not only that, there are some downright freaky things about the hips and torso (look at those super-flat ilia, that enormously deep chest, high shoulders, and the obscenely long pubis - it even looks like a sex beast!) And then there are the arms, which seem to be all humerus! Now to be fair Jaime has previously said that this skeletal has some proportion issues and is not as accurate as it could be, but all the same it's well known that Isisaurus was one weirdly proportioned dinosaur. And at the very least, one of the most extreme necks ever known. That thing was a walking billboard. The neck isn't unusually long for a sauropod (though if the published data is any clue, it was longer than either the torso or the tail). But its extreme depth (along with all the other odd proportions) serves no apparent biomechanical purpose, and it really could only be a product of sexual selection, with the tall spines turning it into a huge display device. Isisaurus was also one of the last dinosaurs to have lived, roaming the jungles of a then-isolated India in the Maastrichtian, right at the end of the Cretaceous. If dinosaurs had not gone extinct 65 million years ago, one can only imagine how much stranger Isisaurus' descendants could have gotten.

But what about feeding adaptations?

While it's entirely possible that some aspects of neck anatomy may indeed have been the result of sexual selection (especially tall neural arches or spines/sails) I doubt that the length or actual mechanics of the neck were influenced so much by sexual selection as by feeding niches. When you lengthen a functional body part like a neck, especially considering it has your head and mouth at the end of it, there are also very practical, non-display considerations.

For example, if you're a ground feeder with peg-shaped teeth and a square "vacuum cleaner" jaw adapted for nipping low ferns, you're probably going to develop a neck which can be held horizontally or even drooping down for long periods of time, and would not be so long as to make maneuvering difficult in at least lightly forested areas. Ordinarily this would put a lot of strain on the neck, but the diplodocids had a way of compensating for this problem - their posterior neural spines were not just heavily forked to support a twin system of cable-like nuchal ligaments - they were also taller relative to vertebra length than on most other sauropods, and heavily angled forward with prominent ball-like ends to add extra leverage to the tendons pulling them back. Thus even in a relatively relaxed position, the nuchal tendons could effectively keep the neck horizontal without over-exerting themselves. The "canyon" between the double rows of neural spines likely included a third, auxiliary set of ligaments, though the knobs which anchored them at the base of these grooves are only prominent in a few genera. This middle tendon was likely not deep enough to entirely fill the space between the double rows of neural spines in diplodocids, and certainly not in dicraeosaurids.

However, if you're a high browser with large heavy teeth and a rounded snout adapted for foraging in the trees, then a long neck is an ideal tool for high feeding in the trees.

In fact it used to be popular to think that all diplodocoids had horizontal necks, all macronarians had vertical necks, etc. Now there is research that disproves both notions. Whitlock has recently come out with a paper that shows that many diplodocids had rounded snout tips and tooth wear patterns consistent with feeding on conifers - including barosaurs like Tornieria and, strangely enough, short-necked dicraeosaurs too (they were probably rearing to feed on the lower branches of the conifers, as they could not reach very high even when rearing). However Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, and Nigersaurus all have square mouths and tooth wear consistent with feeding on low ferns. Nigersaurus seems to have fed exclusively on low ferns, due to its awesomely wide "vacuum cleaner" mouth. It's doubtful this animal ever fed on tough conifers, though it was capable of rearing. It was basically a dinosaurian cow.

Skulls of diplodocoid sauropods seen from above. From Whitlock, 2011. Note the differences in snout shape between mid-level and high browsers (bottom row), low grazers (Apatosaurus and Diplodocus) and UBER-low grazers (Nigersaurus)!

Where else do we see this dichotomy of high-browsing rounded mouths and low-grazing square mouths?

Camarasaurus, Brachiosaurus, Euhelopus all have rounded mouths/snout tips and big heavily worn teeth - the mark of a high browser (and in the case of the huge-mouthed Brachiosaurus and Giraffatitan, a not particularly picky high browser).

But there are some macronarians which have actually "broken the rules" of their clade to become low-grazers and fill in some of the fern-eating niches left vacant in the Cretaceous by the now-extinct diplodocids. Some derived titanosaurs, notably the short-necked Saltasaurus and the even shorter-necked Bonitasaura, have a very diplodocid-like head, and more importantly, square mouths. Antarctosaurus has an extremely wide "vacuum cleaner" mouth that is a remarkable case of convergent evolution with rebbachisaurids like Nigersaurus. All had square snouts and mouths. Yet remarkably, some of their close relatives, the nemegtosaurids, have far longer necks and narrower, round-tipped snouts suited to high browsing. This is a major parallel with the differences of snout design and feeding habits of Diplodocus vs. Barosaurus. It seems that in many different lineages of sauropods, there were both low grazers and high browsers.

However, there's one constant factor (at least more or less constant within most families) that often gets missed. Neck length. Sauropods with vertical feeding habits tend to have much longer necks that low fern eaters - even if they're close relatives. Longer necks are not simply an adaptation for increasing a horizontal ground-level feeding envelope the way proponents of the SNAFU theory ("Sauropod Necks Are Forever Underslung") seem to insist. Barosaurus and Tornieria were high-browsers and they had much longer necks than Diplodocus or Apatosaurus. Furthermore, Apatosaurus is easily twice the mass of Diplodocus, yet has a neck of equal or sometimes shorter length - which proves that as mass increases (and thus your food needs increase) a low-grazer can still consume enough food without needing a proportionally longer neck. In other words, having an extremely long neck when you're a low-grazer is actually a WASTE of precious nutrients and resources that you could be using to feed a bigger body, grow faster to deter predators, etc. As a low-grazing species, once you hit a certain neck proportion, you can get bigger and still keep your neck relatively short (like Apatosaurus) and not have to worry about increasing your feeding envelope beyond that of a far lighter animal like Diplodocus.

Is it really all that hard, after all, to just take a few steps forward when you've consumed everything in your grazing envelope? I thought we'd long moved past the days when sauropods were seen as lazy, lethargic slobs that could barely move their bums at all. The expense of resources for growing a very long neck is too high to justify the increase in feeding envelope size for a sauropod that wasn't even feeding above shoulder level - after all, the limits of lateral mobility on sauropod necks mean that the posterior 75% or so of a horizontal feeding envelope is actually out of reach to a low-grazing sauropod, since the neck can't bend back over its own length like a snake. So the increase in feeding envelope range for horizontal low-grazers with longer necks is marginal at best, since a horizontal feeding envelope isn't really a horizontal cone as commonly depicted in papers - it's more like just the lower half of the base of that cone! A marginal arithmetic increase in this narrow sub-oval arc doesn't justify the huge exponential upfront resource cost of ever longer necks just to avoid the inevitability of having to walk a few steps forward, and that's probably why Apatosaurus's neck was no longer than that of Diplodocus despite being a far more massive and therefore energy-hungry animal. Longer necks are not simply a slothful luxury for low-grazers to get a few more bites while avoiding a few more steps - as such, they would be woefully inefficient in terms of huge extra resource cost vs. the relatively meager benefit of having to walk less - rather, they are an adaptation for something far more specific, something that low-grazing, square-mouthed "vacuum cleaner" diplodocoids didn't even mess with.

Even with advanced 3D computer models, it's clear that low-grazing diplodocid sauropods did not have the extreme neck flexibility to reach the posterior 75% or more of their feeding envelope. Thus every plant in this region was inaccessible to them at any one time. Practically speaking, the envelope is only the front arc of the neck's movement swath, and at most this arc's 3D extent formed only the lower half of a relatively narrow oval. The upper half of a far larger oval envelope would potentially be open to vertical-necked sauropods with longer arms. Image from Stevens, et. al. (1999).

In fact, it's not that far-fetched to say that ALL extremely long-necked sauropods were high browsers. Anything like Brachiosaurus, Giraffatitan, Euhelopus, Omeisaurus, Mamenchisaurus, and many titanosaurs, both basal and derived, would be a high-browser with a neck capable of vertical posture. They all have either massive teeth for crunching through branches, or in the case of barosaurs and nemegtosaurs, tooth-wear patterns and snout shapes that suggest high browsing, perhaps of a more finesse-bound sort. None of these animals have the sharply angled square snout typical of low-grazing fern-eaters.

Skull and mouth shapes of Camarasaurus (C), "Brachiosaurus" (Giraffatitan) brancai (B), Diplodocus (D), Apatosaurus (A), Stegosaurus (E), Indricotherium (I) and some modern animals. From Paul (1998). Note the curved oval mouths/snouts of Giraffatitan and Camarasaurus as opposed to the square, flat-fronted mouths of Diplodocus and Apatosaurus. Posted for educational purposes only.

And logically, an extremely long neck would make maneuvering difficult in tall forests unless it was held vertically or at least semi-vertically. Extremely long tails would make movement in the forest difficult for high-browsers as well, and tails could not be pointed vertically - most high-browsing sauropods simply reduced them. Brachiosaurs are the most extreme example, but there are others. No mamenchisaur or "euhelopodid" ever had a tail comparable in length to that of Diplodocus. And even Barosaurus had a shorter tail than Diplodocus, though both animals were roughly the same size and both had a whip-like tail ending. Thus, extremely long tails (and comparatively short necks) seem to be mainly a feature of low grazing sauropods that fed on the open fern plains, whereas high browers increased the neck (and its typical incline) while reducing the tail, to get at a greater vertical range of food while avoiding getting stuck in the forest. If a complete Supersaurus skull is found, it will probably fit the pattern of high-browsing diplodocids like Barosaurus, even though it's an apatosaurine. It's got the very long neck and relatively modest tail proportions of Barosaurus, and it probably was capable of the same high-browsing behavior - and probably a rounded snout.

Skeletals of Diplodocus carnegiei (F), Barosaurus lentus (G) and Apatosaurus louisae (E) from Paul (1998). Note that Barosaurus has a much longer (and more somewhat vertically capable) neck than Diplodocus, and a proportionally shorter tail (the droopy end of which is missing here). Both the 11-ton Diplodocus and the 20-ton Apatosaurus have fairly modest-sized necks, whereas Barosaurus, which is the same size as Diplodocus, has a far longer neck than either of them. Longer necks are not merely a result of larger size or food needs, and an increase in size and food needs among low-grazers does not correlate with, much less necessitate, longer necks. Posted for educational purposes only.

But what about camarasaurs? They have short necks which can articulate vertically, and they have the snout and teeth of a high-browser - why are their necks not longer? Likely they were not browsing all that high. Like dicraeosaurs, their reach was limited, but could be augmented by rearing. However, it's worthy to note that the teeth of Camarasaurus are more heavily worn than those of some high-browsing sauropods with longer necks. Microwear analysis of these, according to Bakker (1986) indicates they were eating very gritty food, perhaps the result of seasonal dust storms which left grit on the lower levels of conifer trees. As most dust is too heavy to be carried very high, the higher parts of the trees were free from it and caused moderately less wear on the teeth of taller high-browsers. Another possibility is that Camarasaurus was simply a mid-level browser, not a high-browser, and fed on very tough plants like large cycads and the dry lower branches of conifers.

Camarasaurus (upper right, near Allosaurus) had a far shorter neck than Brachiosaurus (large silhouettes, lower left), and even when rearing it could not surpass it in functional height, yet it had the snout tip and teeth of a conifer-eater, not a low grazer. Camarasaurus likely fed on the dry and dust-blown lower branches of conifers, hence its extremely robust and heavily worn teeth (diagram from Paul, 1998 - posted for educational purposes only).

Size and food intake requirements really have nothing whatsoever to do with neck length. "Omeisaurus" tianfuensis is even lighter than the mere 11-ton Diplodocus, yet has a phenomenal neck that absolutely puts it to shame (not to mention Apatosaurus, which weighed roughly 20 tons). Perhaps you could argue that Omeisaurus' crazy-long neck gave it the advantage of a huge vertical AND horizontal feeding envelope - after all, vertical necks imply a full-circle hemispheric feeding envelope, which gives access to far more food at any moment per additional meter of neck than a horizontal wedge-shaped one, regardless of neck flexibility. But in all likelihood, "Omeisaurus" probably didn't need an envelope so big. It was smaller than Diplodocus, (let alone Apatosaurus!) which made do with a much smaller feeding envelope and far less vertical range. Even feeding the extra energy and blood requirements of such a long neck (which might have proved prohibitively high for a low-grazing diplodocid with far tighter vertical limits on its diet and feeding envelope) probably wouldn't require full use of the huge feeding envelope of "Omeisaurus" at every step it walked. After all, the feeding envelope of a 9-ton Omeisaurus was many times the size of that of even a 20-ton Apatosaurus, and far taller as well! It's inconceivable that the neck and heart alone, no matter how large, would somehow use up more nutrients than the 11 additional tons of flesh and bone found in Apatosaurus! So it's unlikely that increasing the feeding envelope was the sole driving force behind some vertical-necked sauropods developing extremely long necks, because many of them probably did not need the entire vertical-capable feeding envelope to meet their energy needs, even with the colossal neck and the powerful heart it required.

The only remaining logical reason for such a dizzying neck is not simply to reach every plant within a vertical-capable neck's entire hemispheric feeding envelope, but to reach a particular food source beyond the reach of shorter necks - most likely the treetops. Extremely long necks are found in both small sauropods like Euhelopus and mega-giants like Sauroposeidon and Puertasaurus. Likewise, relatively short necks are found both on dwarfs like Saltasaurus and giants like Apatosaurus (well, moderately giant anyway). Neck length is more indicative of the type of food you ate and where it was, not how much of it you needed.

"Omeisaurus" tianfuensis. This highly specialized Chinese sauropod, known from better remains than true Omeisaurus, was even lighter and smaller-bodied than Diplodocus, but had a far longer neck and larger potential feeding envelope despite its likely lower food needs. Note the low, posteriorly oriented neural spines and long overlapping cervical ribs typical of all vertical-necked sauropods, regardless of their time period or lineage. Its head is large and round-snouted, typical of high feeders. The club-tipped tail is also fairly short, which makes this an ideal maneuverable design for feeding in dense forests. From an unpublished Greg Paul skeletal, ~1995. Posted for educational purposes only.

Giraffatitan, Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, Indricotherium, Steppe Mammoth, and African elephant skeletals by Greg Paul. Notice how Apatosaurus is more massive than Diplodocus but actually has a shorter neck with much the same horizontal configuration, strange retrograde-tilted neural spines, etc. For educational purposes only. In Giraffatitan and other vertical-necked sauropods (even totally unrelated ones), the spines and cervical ribs have quite a different configuration. Posted for educational purposes only.

End result: Mamenchisaur necks vertical, Macronarian necks vertical (except for saltasaurids and a few other derived titanosaurs), diplodocid necks horizontal (possibly except barosaurines and Supersaurus) and dicraeosaurid necks horizontal but still vertical-capable by rearing. BTW the diplodocid neck mechanics of barosaurs and Supersaurus still would not allow as sharp an incline as in most macronarians. They could have curved the neck up at roughly 45 degrees or reared up like other diplodocids to get at the very high branches. While rearing, these high-browsing diplodocids would have towered over even Brachiosaurus.

Long story short, necks may have served a sexual display or species recognition function, but that alone is insufficient to explain actual neck length differences, which are largely feeding-related. Sex alone cannot justify the vast expenditure of nutritional resources needed for developing some of the longest sauropod necks, as these were energy-costly flesh, blood, and bone structures, rather than simple keratinous cosmetic features like peacock feathers, which are not an integral part of internal anatomy and require far less food intake to maintain. Though sauropod necks were not long simply for sexual reasons, some secondary features of the living neck (such as color and possible display spines) may have had a sexual display purpose. Also, unusual neck width and depth are likely sexually selected display features, particularly in extreme forms like Isisaurus. However, functional length and flexibility were likely free of sexual driving forces for the most part, and were more driven by feeding specializations. Very long necks for high browsers, shorter ones for medium or low browsers. Low shoulders + relatively short neck usually equals low-grazer, but not in the case of Dicraeosaurus. Ultimately, skull and snout shape is one of the best gauges of sauropod feeding habits, and indicates that very long necks are always associated with high browsers, but that not all shorter necks are those of low-grazers.

Say what? I'll show you what a droopy neck looks like!

Of course, Taylor, Wedel, and Naish (2009) have already pretty much busted the myth that sauropods couldn't have raised their necks vertically. They showed (using biomechanical comparisons with living animals, no less!) that sauropod necks can have a substantial range of articulation in each joint well above Osteological Neutral Pose - these were flexible ball-and-socket joints, not stiff flat-ended ones. Indeed, for low-spined forms with very long necks like brachiosaurs and mamenchisaurs, a vertical posture would be far easier to hold up than a horizontal one since the shallow nuchal tendons would be quickly strained in a horizontal posture - imagine holding a long pole at one end horizontally, you can't. Vertically, you can, since gravity is now working with you, not against you. Simple. Diplodocus managed a horizontal posture thanks to its deep and strangely forward-angled "cantilever" neural spine yokes, giving more passive leverage to the nuchal tendons to keep the neck in a horizontal position without over-straining. Barosaurus is an odd case - with its longer neck, would have probably had a steeper habitual neck posture (as illustrated in Paul, 1998) to minimize strain, but the same cantilever design in its lower cervicals meant that they too started off horizontal as in Diplodocus. If it fed while rearing (which was very likely) it would reach great heights without needing to deflect the neck up relative to the back.

In other words, proportional neck length is related to feeding niches, not sex or size/calorie requirements. Long necks for high browsers, shorter ones for medium and low browsers. Macronarians and mamenchisaurs likely used vertical posture to reach food at their particular browsing level, while diplodocoids either reared to reach high, or didn't even bother and just stuck to ferns and seedlings. And if you're still drawing your brachiosaurs or mamenchisaurs with droopy horizontal or underslung necks sticking out like a microphone boom on a movie set - crane 'em up!

*

*